This article written by Lloyd Axworthy and Allan Rock was originally published in The Globe & Mail.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau recently co-chaired with UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres a global gathering to encourage financial aid for countries in the global south to cope with the pandemic and its aftermath. At the same time, international financial institutions are pledging to massively increase the sums available to assist developing states in their recovery.

We have a heavy moral obligation to provide such assistance as developing countries struggle to care for those infected and to recover from the economic impact of the coronavirus. So all of this is very good news. But it is necessary to add a note of caution. The World Bank estimates that every year, corrupt officials worldwide steal US$20-billion to US$40-billion from money intended as development assistance. While Canada and other donors hasten to make the much-needed aid available, we must surely be concerned to limit the amounts that will fall into the wrong hands.

Now, corruption is not limited to developing countries. Its insidious taint is seen worldwide. But some of the most notoriously corrupt governments are among those that are most likely to receive the lions’ share of pandemic-related aid.

Two recent and innovative proposals might help. Each of them is designed to deal with political corruption: to deter it, to detect it, and to punish it.

The first is a recommendation from the World Refugee & Migration Council relating to frozen assets. The Council proposes that countries should not only freeze purloined assets found in their jurisdictions, but also adopt legislation permitting a court order authorizing the confiscation of those assets and their repurposing for the benefit of refugees in cases where there is not a trustworthy government to receive the funds back.

The idea is to introduce accountability for the thieves and generate much-needed resources for refugee services.

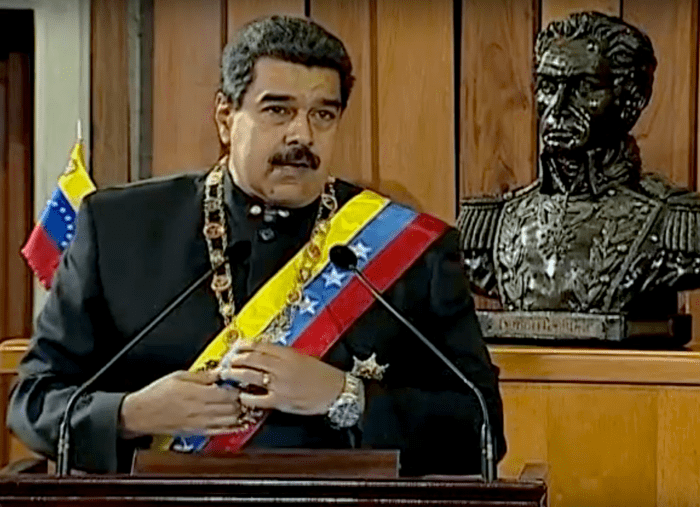

The idea is to introduce accountability for the thieves and generate much-needed resources for refugee services. Take the example of Venezuela. Suppose Nicolas Maduro deposited cash in Canadian banks. Under the Council proposal, that money would not only be frozen, but could be seized and used for the benefit of the millions of Venezuelans driven from their homes into neighbouring states by Mr. Maduro’s violent and oppressive regime. Such an approach would provide accountability and help fund the refugee housing and social services that Venezuela’s neighbours cannot afford to provide.

The Trudeau government has pledged to enact the proposed legislation, and depending on the availability of time in the Parliamentary calendar, it could be adopted this year or next.

The second proposal is to create a new global institution called the International Anti-Corruption Court (IACC). It would have authority to investigate, prosecute and punish grand corruption – the abuse of public office for private gain by a country’s leaders and their collaborators. It would operate on the principle of complementarity: the court would exercise its authority to prosecute only if a country was found to be unable or unwilling to prosecute its leaders itself.

Some argue that the IACC would be hobbled because the rogue states that are the main corruption offenders would never join it. That may be true, but kleptocrats in such countries do not keep their stolen money at home. So if the IACC member states include financial hubs, such as Switzerland and Singapore, and the destinations the crooks prefer when they are looking for a safe place to stash the cash, such as Canada and the United Kingdom, then the IACC would have jurisdiction to investigate and prosecute when sums are deposited there.

Setting up the IACC would require a treaty, which means a “critical mass” of UN member states would have to sign on. The leading advocate for the new court is Mark L. Wolf, a senior U.S. District Court judge and chair of the anti-corruption organization Integrity Initiatives International. Inspired by Mr. Wolf’s compelling vision, a grassroots effort has emerged, similar to the Canadian-led process that resulted in the agreement on banning landmines known as the Ottawa Treaty more than 20 years ago. High-level officials in Colombia, Ukraine and Nigeria are already supportive, and some are pushing to have the United Nations commit to creating the court at a 2021 special session on corruption. Other supporters include a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, members of the U.S. Congress, leading non-governmental organizations, and courageous young people whose indignation at grand corruption has ousted kleptocrats in Ukraine and other countries.

Canada can make a meaningful difference by adding its support to the growing anti-corruption movement throughout the world. What better time to pursue this objective than now, when immense sums are about to flow to vulnerable governments to help deal with the pandemic’s major economic and social impact.

Let’s make sure that those dollars get to where they are needed most, and are not skimmed off the top by dishonest officials looking only to enrich themselves.