Ninette Kelley was recently appointed chair of the World Refugee & Migration Council and was previously a senior UNHCR official. Her recent book is Reshaping the Mosaic: Contemporary Canadian Immigration Policy with Michael Trebilcock and Jeffery Reitz. This op-ed was first published by The Hill Times.

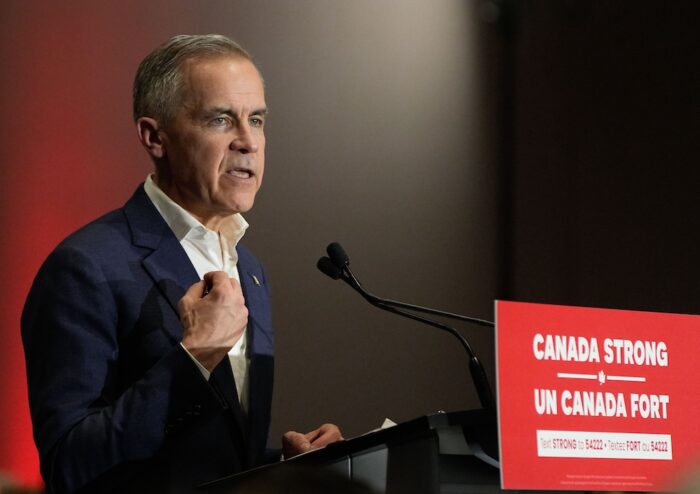

During the 2025 election campaign, Prime Minister Mark Carney promised global leadership in protecting human rights defenders and refugees. The apparent retreat from this commitment by his government is rapid and troubling.

Within months, his government moved to restrict access to asylum in Canada, reduce overseas refugee selection, pause private sponsorship, and further tighten admission of asylum seekers arriving via the United States.

The Strong Borders Act (Bill C-12), before Parliament, would grant the Minister of Immigration sweeping “public interest” powers to cancel, suspend, or alter immigration documents—including visas, permanent and temporary resident permits—and to halt new applications, resembling the authorities President Trump is exercising in the United States. It is among the most controversial and arguably undemocratic aspects of the Bill.

The Bill would also bar hearings before the Immigration and Refugee Board to those who apply for asylum more than one year after arrival and require those entering through unofficial border crossings to file asylum claims within 14 days. Advocates rightly argue for the legislation to include exceptions where delays are justified. An Afghan woman studying in Canada whose student visa was prematurely cancelled is an obvious example.

These restrictions build on the 2004 Canada–U.S. Safe Third Country Agreement, which requires asylum seekers to seek protection in the first country they enter, subject to narrow exceptions for unaccompanied minors, family ties, valid entry documents, and limited public-interest grounds under Canadian law.

Originally applied only at official land crossings, the agreement was extended to the entire border in 2023. The effect was immediate: asylum claims by those crossing irregularly fell from some 40,000 in 2022 to fewer than 1,400 in 2024.

Safe third-country arrangements rest on two principles: that refugees do not have an unfettered right to choose their asylum country and that removal is permitted only if the other state offers a fair adjudication process and protection from refoulement (return to a country where a person faces a serious risk of persecution).

Current harsh and punitive asylum practices in the U.S. call this second condition into question—though not, it seems, for Canada’s Minister of Immigration, Lena Diab, who recently said that the government is “comfortable” in continuing to honour the Agreement.

The response is glaring in its lack of empathy and inadequate given the very serious events unfolding in the U.S. and the challenges they pose for Canada.

Last week President Donald Trump referred to Somalis as “garbage” and unwelcome, while days earlier the administration paused all asylum decisions following the shooting of two National Guard officers: the suspect an Afghan immigrant. It subsequently froze the granting of legal status (asylum, permanent residency, naturalization) and other benefits like work authorizations to nationals of 19 “high risk” refugee producing countries.

These follow a series of measures to deter and restrict asylum, including expanded mandatory detention, higher screening thresholds, accelerated processing, and faster removals, including of people granted protection to third countries where they may be mistreated.

The constitutionality of the Safe Third Country Agreement is being litigated in Canada. Although the Supreme Court of Canada previously upheld the designation of the United States as a safe third country, the asylum system in the US today is so different that the outcome of the constitutional challenge may differ.

Advocates argue that removing asylum applicants to the U.S. during the current crackdown makes Canada complicit in human-rights violations it condemns. Others warn that scrapping the agreement could provoke U.S. retaliation and overwhelm Canada’s asylum system.

Both concerns have merit.

As Canada negotiates a new trade policy with the United States, President Trump often describes actions inconsistent with his administration’s approach as security risks, and Secretary of State Marco Rubio has instructed U.S. diplomats to press countries on the “dangers” of migration.

How should Canada navigate these tricky waters?

First by ensuring that the exceptions to the Safe Third Country Agreement are applied consistently and fairly and by providing guidance on the application of the exceptions for those in immediate risk.

Second, by capitalizing on the growing number of U.S. citizens and permanent residents who are seeking to emigrate: enhancing selection from the U.S. across economic, family, and refugee-resettlement streams. Plans to fast-track highly skilled U.S. visa holders is a start.

Finally, the Government must reform Canada’s refugee determination system. The backlog of close to 300,000 cases reflects growing global forced displacement, a surge of inland claims following abrupt temporary visa reductions, unnecessary procedural complexity, and too few adjudicators. A system that processes cases faster yet fairly is urgently needed.

More people need protection than Canada can accommodate. But this is no reason to remain complacent. Canada can do much more to live up to the Prime Minister’s protection promise. Remaining “comfortable” is not one of them.

Photo: © Shutterstock/Harrison Ha