Education is important to all children, but for refugee children schools provide not only learning opportunities but also safe spaces and a semblance of normalcy in young lives turned upside down by conflict and displacement. Education can serve to build community and contribute to peacebuilding, which I look forward to exploring in our Refugees, Education and Conflict panel discussion this week about the important role that education plays in the lives of refugees.

This issue is particularly relevant as we think about the one-two punch refugees have experienced over the past year. Not only are they fleeing new conflicts or living in limbo as conflicts drag on for years, but they have been particularly hard hit by the measures taken to control the coronavirus pandemic. These measures have affected day-to-day life in almost every aspect. But on this International Day of Education we are particularly conscious of COVID-19’s impact on education.

2020 was a terrible year for education in every country on the planet. Everywhere students struggled with internet connections to access online platforms, teachers spent hours trying to translate curricula into zoom formats, and parents wrestled with constantly changing school schedules. Many students, particularly in marginalized communities, dropped out of school — sometimes because they didn’t have bandwidth or tablets, often because they had to work to support their families who were suffering the harsh economic costs of lockdowns and widespread layoffs. Indeed UNICEF estimates that 1.6 billion students worldwide have been affected by the COVID-19 lockdowns.

Education provides hope to people whose lives have been upended and put on hold. Even in these dark pandemic times, we have to make sure that education — and hope — continue.

The impact of COVID-19 on refugee students is particularly dire. Even before the pandemic, refugee children struggled to access education. UNHCR has noted that around half of the world’s refugee children were not in school before the COVID-19 restrictions In 2019: about two-thirds of refugee children were in primary school, about 20 percent were in secondary school and less than 2 percent had access to university education. Even when they were able to access schools, they faced other barriers to education, including the effects of trauma and the fact that most had missed school because of their displacement. COVID-19 has disproportionately affected refugee children’s access to education — both those living in camps and those living in other settings.

Refugee girls have always had a harder time enrolling and staying in school than boys. Using UNHCR data, the Malala Fund predicts that half of all refugee girls are unlikely to return to secondary school after the COVID-19 restrictions end. This will have dire consequences for the girls themselves, but also for their communities and families in the years to come.

COVID-19 is not only making it more difficult for refugee and displaced children to access education, but it is also leading to greater poverty, hunger and insecurity — all of which make education even more difficult for children and young people. The World Food Program and the International Organization for Migration reported dramatic increases in food insecurity in developing countries as a result of COVID-19 disruptions and found that nine out of ten of the world’s worst food crises are in countries with the largest numbers of internally displaced persons.

Refugee education is not a luxury. Anyone who has talked with refugees in the field knows how important education is to refugee students and their parents. Education provides hope to people whose lives have been upended and put on hold. Even in these dark pandemic times, we have to make sure that education — and hope — continue. The long-term consequences of cutting back on education are simply too dire to contemplate.

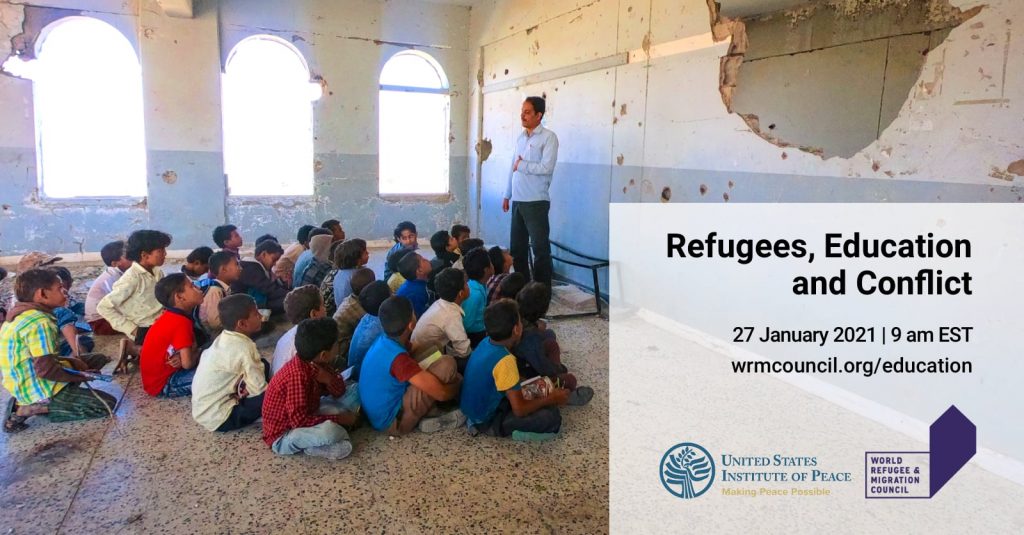

Photo: Children attend class in Azez, Syria. (Shutterstock)